Les míserables — Part I Book I Chapter 2

Chapter 2 — M. Myriel Becomes Monseigneur Bienvenu

The episcopal palace of Digne was adjacent to the hospital.

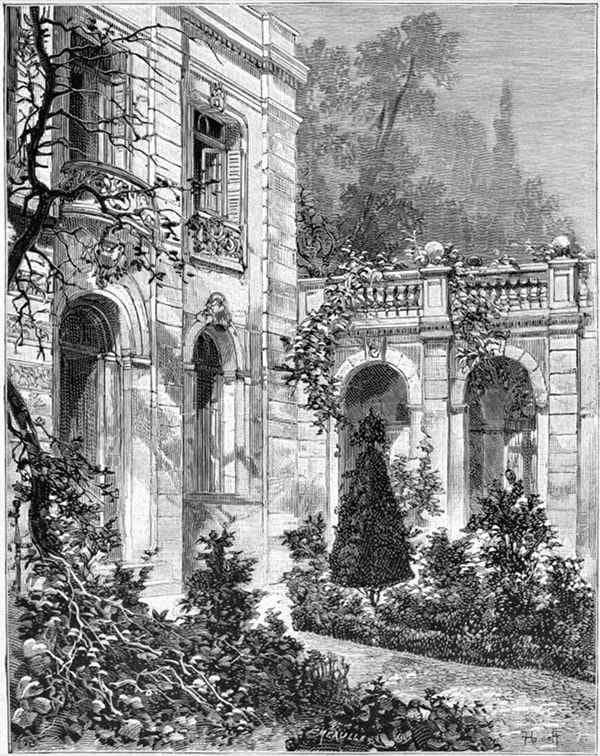

The episcopal palace was a spacious and beautiful mansion built of stone at the beginning of the previous century by Monseigneur Henri Puget, Doctor of Theology of the faculty of Paris, Abbé of Simore, who was Bishop of Digne in 1712. This palace was a true lordly residence. Everything about it had a grand air: the bishop’s apartments, the halls, the bedrooms, the main courtyard—very large, with arched walkways after the classic Florentine fashion—the gardens, planted with magnificent trees. In the dining hall—a beautiful long gallery situated on the ground floor and looking out on the gardens—Monseigneur Henri Puget had hosted a ceremonious formal dinner on July 29, 1714, for Monseigneurs Charles Brûlart de Genlis, Archbishop-Prince of Embrun; Antoine de Mesgrigny, Capuchin and Bishop of Grasse; Philippe de Vendôme, Grand Prior of France and Abbé of Saint-Honoré of Lérins; François de Berton de Grillon, Bishop-Baron of Vence; César de Sabran de Forcalquier, Bishop-Lord of Glandève; and Jean Soanen, priest of the oratory, preacher in ordinary to the king[21] and Bishop-Lord of Senez. The portraits of these seven reverend dignitaries adorned that hall, and that memorable date, “July 29, 1714,” was engraved there in gold letters on a white marble plaque.[22]

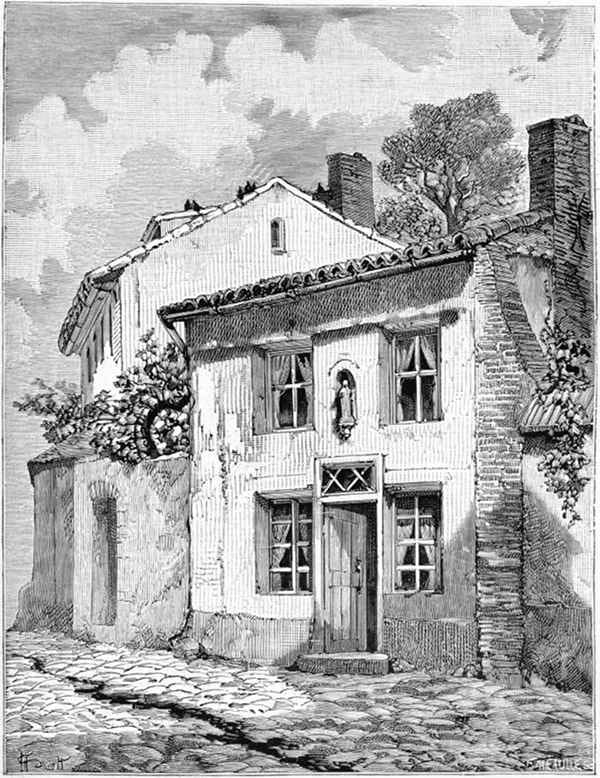

The hospital was a narrow and squat single-story building with a small garden.[23]

Three days after his arrival, the bishop visited the hospital. The visit complete, he asked the director to kindly step over to his house.

“Monsieur Director,” he said to him, “how many patients do you have right now?”

“Twenty-six, Monseigneur.”

“That’s what I counted,” said the bishop.

“The beds,” continued the director, “press tightly against each other.”

“That’s what I noticed.”

“The wards are nothing but small bedrooms, and poorly ventilated.”[24]

“That’s how it seems to me.”

“And then, when there is a ray of sunshine, the garden is very small for the convalescents.”

“That’s what I told myself.”

“During epidemics—we’ve had typhus fever this year, and miliary fever[25] two years ago, sometimes a hundred patients—we don’t know what to do.”

“That’s the thought that came to me.”

“What do you expect, Monseigneur?” said the director. “We must resign ourselves to it.”

This conversation took place in the dining hall on the ground floor.

The bishop remained silent for a moment, then he turned abruptly toward the hospital director.

“Monsieur,” he said, “how many beds do you think this hall alone would hold?”

“Monseigneur’s dining hall!” exclaimed the stupefied director.

The bishop’s gaze was roaming about the hall, and he seemed to be taking measurements and making calculations with his eyes.

“It would hold a good twenty beds!” he said, as if speaking to himself; then raising his voice:

“Look here, Monsieur Director, let me say something. There’s obviously a mistake. You have twenty-six people in five or six small rooms. Here there are three of us, and we have space for sixty. There’s a mistake, I tell you. You have my house, and I have yours. Give me back my house. This is your home.”

The next day the twenty-six poor convalescents were installed in the bishop’s palace, and the bishop was in the hospital.

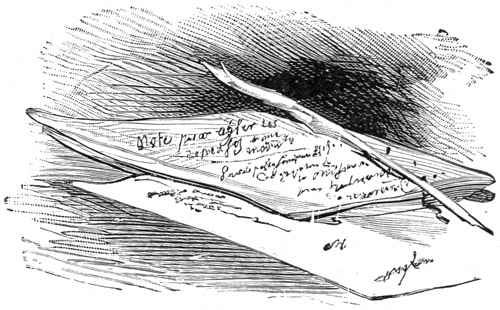

M. Myriel had no property, his family having been ruined by the Revolution. His sister received a lifetime annuity of five hundred francs, which, living at the vicarage, covered her personal expenses. As bishop, M. Myriel received a salary of fifteen thousand francs from the state. The same day that he moved into the hospital, M. Myriel settled on the use of this sum, once and for all, in the following manner. We transcribe a note here in his own handwriting.

A Note to Organize my Household Expenses.[26]

For the secondary church school 1,500 livres.

Congregation of the Mission 100 livres.

For the Lazarists of Montdidier 100 livres.

Paris Seminary for Foreign Missions 200 livres.

Congregation of the Holy Spirit 150 livres.

Religious establishments in the Holy Land 100 livres.

Societies for Maternal Charity 300 livres.

In addition, for the one in Arles 50 livres.

Work for the improvement of prisons 400 livres.

Work for the relief and deliverance of prisoners 500 livres.

For the liberation of fathers of families who are

imprisoned for debt 1,000 livres.

Supplements to the salary for poor schoolmasters

of the diocese 2,000 livres.

Public granary of the Upper Alps 100 livres.

Congregation of the Ladies of Digne, of Manosque and

Sisteron for the free education of indigent girls 1,500 livres.

For the poor 6,000 livres.

My personal expenses 1,000 livres.

______

Total 15,000 livres.

During the entire time that he occupied the diocese of Digne, M. Myriel changed almost nothing about this arrangement. He called it, as we’ve seen, “Organizing my household expenses.”

This settlement was accepted with absolute submission by Mademoiselle Baptistine. For that blessed woman, M. de Digne was at the same time her brother and her bishop, her friend according to nature, her superior according to the church. She quite simply loved and venerated him. When he spoke, she bowed; when he acted, she followed. Only the servant, Madame Magloire, grumbled a bit. M. the Bishop, one may have noticed, reserved only a thousand livres for himself; combined with Mademoiselle Baptistine’s pension, that made fifteen hundred francs a year. Those two old women and that old man lived on that fifteen hundred francs.

And when a village curé came to Digne, M. the Bishop still found the means to be his host, thanks to the strict economy of Madame Magloire and the intelligent administration of Mademoiselle Baptistine.

One day—he had been at Digne for about three months—the bishop said:

“With all this I’m in very tight straits!”

“I should think so!” exclaimed Madame Magloire, “Monseigneur hasn’t even claimed the allowance the department owes him for his carriage costs in town and his rounds in the diocese. That was the custom for bishops in former times.”

“Well!” said the bishop, “You’re right, Madame Magloire.”

He put in his claim.

Some time afterwards, the General Council, taking this request under consideration, voted him the annual sum of three thousand francs, under this heading: “Allowance to M. the Bishop for costs of a carriage, post horses,[27] and pastoral rounds.”This stirred up a great outcry among the local bourgeoisie, and given that opening, a senator of the Empire—a former member of the Council of the Five Hundred,[28] in favor of the 18th Brumaire,[29] and provided with a magnificent senatorial office near the town of Digne[30]—wrote a short, angry, and confidential note to M. Bigot de Préameneu,[31] the minister for religious communities, a note from which we excerpt these authentic lines:

“Carriage costs? What for, in a town of less than four thousand residents? Costs of post horses and pastoral rounds? To begin with, what’s the point of those trips? And next, how are the posts to run in a country of mountains? There are no roads. You can only travel on horseback. Even the bridge over the Durance at Château-Arnoux can barely support oxcarts.[32] These priests are all like that; greedy and rapacious. This one here played the good apostle when he arrived. Now he acts like the others, he must have his coach and post-chaise.[33] He must have luxuries just like the old-time bishops. Oh! All these papists! Monsieur Count, things won’t go well until the emperor delivers us from the skullcaps. Down with the pope!” (Affairs with Rome were heating up.)[34] “As for me, I’m for Cæsar alone.” Etc., etc.[35]

In contrast, the affair greatly delighted Madame Magloire.

“Good,” she told Mademoiselle Baptistine, “Monseigneur began with others, but he must surely finish with himself. He’s taken care of all his charities. Here are three thousand francs for us. At last!”

That very evening, the bishop wrote out and handed his sister a note reading as follows:

Carriage and Rounds Expenses.[36]

To provide meat bouillon to the patients in the

hospital 1,500 livres.

For the Maternal Charitable Society of Aix 250 livres.

For the Maternal Charitable Society of Draguignan 250 livres.

For foundlings 500 livres.

For orphans 500 livres.

______

Total: 3,000 livres.Such was M. Myriel’s budget.

As for incidental episcopal fees—marriage bans, dispensations, baptisms, sermons, consecrations of churches and chapels, marriages, etc.—the bishop collected these all the more roughly from the wealthy because he gave them to the poor.

After a little while, offerings of money flooded in. Those with and those without knocked at M. Myriel’s door, some coming to seek the alms that the others came there to deposit. In less than a year the bishop became the treasurer for every generous act, and the cashier for every distress. Some considerable sums passed through his hands, but nothing could make him change anything in his way of life, or add the smallest superfluity to his necessities.

Far from it. Since there is always even more wretchedness at the bottom than there is brotherhood at the top, everything was given, so to speak, before being received; it was like water on dry soil; no matter how much money he received, he never had any. So he stripped himself.

The custom being that bishops place their baptismal names at the head of their edicts and pastoral letters, the poor people of the district, with a sort of affectionate instinct, had selected from their bishop’s names and surnames the one that furnished them some meaning, and they called him Monseigneur Bienvenu.[37] We’ll do like them, and we’ll call him thus on occasion. Besides, this name pleased him. “I like that name,” he said. “‘Welcome’ softens the ‘Monseigneur.’”

We don’t claim the portrait we’ve drawn here is plausible; we confine ourselves to saying that it’s true to life.[38]

Footnotes

[21] “Oratory” in this context refers to the French Oratory, a congregation of priests (1611 to current day) concerned with what they saw as the waning of spirituality in the Catholic priesthood. “Preacher to the king” was an honorary title given to priests who had been invited to preach a sermon to the king and royal court. “Preacher in ordinary to the king,” oddly, was a loftier title, meaning a priest who had preached an Advent or Lent sermon.

[22] This appears to be a tedious enumeration of unknown, perhaps even fictional, clerics, but the seven “reverend dignitaries” are all historical figures, and they appear to have been selected and listed in this particular order to imply a point. Henri du Puget (1655-1728) was the Bishop of Digne from 1708-1728. Charles Brûlart de Genlis (1628-1714) was the Archbishop of Embrun from 1668-1714; he also held the title of Prince of Embrun. Joseph-Ignace-Jean-Baptiste (but not Antoine) de Mesgrigny (1653-1726) was the Bishop of Grasse from 1711-1726. Philippe de Vendôme (1655-1727) was named grand prieur de France of the Order of Malta at the age of only 23. François de Berton des Balbes de Crillon (1648-1720) was the Bishop of Vence from 1707-1714 (and then the Archbishop of Vienna from 1714-1720). César de Sabran (c. 1642-1720) was the Bishop of Glandève from 1702-1720. Jean Soanen (1647-1740) was the Bishop of Senez from 1696-1727.

The seven guests all hailed from within 75 miles from Digne; here is the map from the previous chapter, updated with their home cities and towns, as well as a few other places that will come up later in the chapter:

One of these men, however, was not like the others; and by placing this man at the end of the list, Hugo seems to be reminding us that not all bishops are cut from the same cloth. Jean Soanen had been a brilliant and influential preacher in his youth. He had earned his title of “preacher in ordinary to the king” with Lent sermons in 1686 and 1688, and in 1696 King Louis XIV had named him Bishop of Senez. Senez was one of the smallest, most remote dioceses in France, and there—far removed from the brilliant society of the Parisian court—Soanen became known, from one account, as “a venerable prelate ... who led an apostolic life among his simple-minded flock in a remote and thinly peopled district in the mountains of Provence.”

Late in his life, however, Soanen became more widely known for his support of Jansenism, a theological movement that emphasized man’s need for divine grace. This position was seen as dangerously close to that of Protestant leaders like John Calvin, and the Jansenist movement was condemned in a 1713 papal bull. Despite his quasi-exile to Senez, and despite being in his 70s, he became one the leaders of a formal clerical protest against the bull. This stand led to his formal summons to the Council of Embrun in 1727, where a group of other bishops dismissed him from his diocese. Soanen spent the rest of his life in even greater oblivion, imprisoned for 13 years in the Chaise-Dieu abbey, and buried in an unmarked grave within a private chapel so that Soanen’s followers would be unable to mourn him.

[23] Note that in France the floor numbers start with what in the United States would be called the second floor, so “single-story” means the hospital has a ground floor and one story above that.

[24] In the French, this is a paradoxical contrast between two apparently similar things: Les salles ne sont que des chambres (literally: “The rooms are only bedrooms”). One of Hugo’s favorite antithetical devices is to draw a contrast like this between two relatively similar concepts, as a way to focus our attention on the respects in which they differ. These contrasts are often difficult to translate, as there may not be English words that capture the same combination of similarity and nuanced difference; this translation strives to underscore the contrast.

In French, the difference between salle and chambre is primarily one of size and purpose; a salle might refer to an open hall, ballroom or dining hall, while a chambre would usually refer to a bedroom. In the context of a hospital, a salle would be a large room with a number of hospital beds—a ward. And at this epoch, a bedroom would often be a small room, perhaps no more than a windowless alcove, in order to better retain heat overnight in cold weather.

[25] The disease la suette miliare—“miliary fever” or “sweating sickness”—would have been familiar to Hugo’s readers in 1862, but not to modern readers. The TLFi (Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé, a French language resource comparable to the Oxford English Dictionary) defines it as “A contagious and epidemic febrile illness, of unknown origin, characterized by an abrupt elevation in temperature, accompanied by copious and excessive sweating, by a cutaneous outbreak (consisting of small red papules covered with small whitish blisters), by nervous disorders and by difficulty breathing.” August Hirsch’s “Handbook of Geographical and Historical Pathology” (1883) describes it as a highly infectious disease responsible for almost 200 outbreaks in France between 1718 and 1879 as well as many more in England, Germany and Italy, albeit under other names. Those infected almost always recovered within 1-2 weeks, but some outbreaks were characterized by atypical mortality rates as high as 20%.

[26] Myriel’s memo mentions three new place names, Arles, Manosque and Sisteron; they are shown on the map above. Arles lies on the Rhône River, near the western border of the Bouches du Rhône department. Sisteron and Manosque lie on or near the Durance River in the Lower Alps.

The note lists the various sums in livres; this is a French unit of value dating back to the reign of Charlemagne. The franc mentioned in earlier paragraphs is the name of a 1 livre coin. Anticipating future references to French currency: 1) the sou is a coin worth 1/20th of a livre; 2) the écu is a 5 livre coin; 3) the louis or napoleon is a 20 livre coin (those minted under the Empire bore a portrait of Napoleon, those issued under the monarchy bore a portrait of the reigning Louis); 4) the liard is a coin worth a quarter of a sou, or 1/80th of a livre). 5) A centime is a coin worth 1/100th of a livre.

Finally, and most importantly, this note says a great deal about M. Myriel’s priorities. Clarifying a few of the line items: “Secondary church school” is petit séminaire in the French; this is a term used to refer to secondary schools run by the Roman Catholic church. The “Congregation of the Mission” is a Roman Catholic institution, also referred to as the “Lazarists” (see the subsequent item), formed for the purpose of providing religious instruction to the poor in France and abroad. The “Societies for Maternal Charity” refers to a number of organizations formed to help working mothers.

Much of M. Myriel’s charity, therefore, is driven by three concerns: the plight of incarcerated men in the French prison system, the plight of mothers struggling to live and raise children without the help of husbands and fathers, and above all, the need for education for children. These concerns echo and concretize the issues Hugo raised in his preface, namely: “the degradation of man through systematic destitution, the debasement of woman through hunger, and the atrophy of childhood through darkness.”

One final point: Myriel lives on 10% of his income and gives away 90%—the exact opposite of a traditional 10% tithe. Hugo scholar Guy Rosa points this out in his annotated French edition of Les misérables, calling it a dîme inversée (“reverse tithe”).

[27] The term “post horses” refers to the institution of a network of stables, from which horses were available for rent to either riders or travelers in private carriages, as well as to support commercial carriages and the mails.

[28] The “Council of the Five Hundred” was the lower house of the French legislature during the latter part of the French revolutionary period.

[29] “18 Brumaire” was the date (in the French republican calendar) of the 1799 coup in which Napoleon dissolved the Council and named himself First Consul.

[30] The significance of these details is that they add up to a portrait of the senator as an expedient politician who has expertly surfed the tides of historical change—a Revolutionary legislator turned Bonapartist—and in consequence enjoys the perks of legislative office under the Empire.

[31] Félix-Julien-Jean Bigot de Préameneu (1747-1825) was minister of religious affairs from 1808-1815 under Napoleon’s reign.

[32] Château-Arnoux is a town several miles west of Digne on the Durance River; it’s shown on the map above. It would be necessary to cross the bridge there to travel to Digne’s pastoral communities beyond the river to the west, such as Sisteron and Manosque.

[33] A chaise de poste (“post-chaise”) is a small closed coach, seating 2-4 people, pulled by post horses.

[34] At the time this letter was written (in 1806 or 1807) relations between Napoleon and the Vatican had begun to deteriorate again (see notes to P1B1Ch1), specifically with regard to the precedence of state over spiritual authority.

[35] The senator is railing against the Catholic Church to express his support of the Empire in that same dispute. “I’m for Cæsar alone” is a reference to Matthew 22:21: “... Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s.” (King James Version)

[36] The new list mentions two place names, Aix and Draguinan. Aix has already come up in I.i.1 (it is the site of the legislative council in which Myriel’s father served.) Draguinan is the administrative center for the department of Var. They are both shown on the map above.

[37] Recall that “Bienvenu” is one of M. Myriel’s several names; the word also means the greeting “Welcome” in French.

[38] In the French, Hugo finds an antithetical contrast between vraisemblable (“plausible” or “likely”) and ressemblant (“lifelike”)—two words sharing the etymological root semble, but having significantly different meanings.

© 2023 Steve Wright