Les misérables - Part I Book I Chapter 10

Chapter 10 — The Bishop in the Face of an Unfamiliar Light

At a time a little later than the date of the letter quoted in the preceding pages, he did something even more dangerous, according to the entire town, than his trip through the bandits’ mountains.

In the countryside near Digne there was a man who lived all alone. This man was—let’s say the offensive word at once—a former conventionalist.[136] His name was G.[137]

In the small world of Digne they spoke of the conventionalist G. with a kind of horror. A conventionalist—imagine that? He had existed at the time when they called one other tu[138] and when they said: “citizen.”[139] This man was more or less a monster. He hadn’t voted for the death of the king, but nearly so.[140] He was a quasi-regicide. He’d been dreadful. How was it that this man hadn’t been taken before the provost court on the return of the legitimate princes? They needn’t have cut off his head, if you like—there must be clemency, very well—but a good banishment for life. An example, in short! Etc., etc. Besides, he was an atheist, like all those folks then. The gossip of geese about a vulture.

However, was he a vulture, this G.? Yes, if he were judged by the feral nature of his solitude. Not having voted for the king’s death, he hadn’t been included in the decrees of exile, and had been able to remain in France.[141]

He lived three quarters of an hour from the town, far from every hamlet, far from every road, in God only knows what hidden recess of an overgrown valley. It was said he had a sort of field there, a hole, a lair. No neighbors, not even passersby. Since he’d dwelt in that valley, the trail that led there had vanished beneath the grass. They spoke of that place like the executioner’s house.

The bishop thought of it, however, and from time to time he gazed at the horizon at the place where a clump of trees marked the old conventionalist’s valley, and he said: “There’s a soul over there who is all alone.”

And in the depths of his thoughts he added: “I owe him a call.”

But let’s admit it: this idea, natural at first sight, seemed strange and impossible to him after a moment of reflection, and almost repulsive. For deep down he shared the general impression, and without his being clearly aware of it, the conventionalist inspired in him that sentiment that borders on hate and is expressed so well by the word antipathy.[142]

Should the sheep’s mange make the shepherd back away? No. But what a sheep!

The good bishop was in a quandary. Sometimes he set forth in that direction, then he came back.

At last one day the rumor spread through the town that a sort of young shepherd, who served the conventionalist G. in his hovel, had come in search of a doctor; that the old scoundrel was dying, that paralysis was overcoming him, and that he wouldn’t live through the night. “Thank God!” some added.

The bishop took his staff, put on his overcoat—owing to his worn-out cassock, as we’ve said, and also because of the evening wind, which would begin blowing before long—and set out.

The sun was setting and had nearly touched the horizon when the bishop reached the proscribed location. He recognized with a certain pounding of his heart that he was near the lair. He stepped over a ditch, clambered over a hedge, raised a gate, entered a small, dilapidated garden, took a few rather bold steps, and suddenly, at the edge of a fallow patch, behind a high thicket, he caught sight of the den.

It was a very humble hut, poor, small, and clean, with a trellis nailed to the façade.

In front of the door, in an old chair with wheels, a peasant’s armchair, there was a white-haired man who was smiling at the sun.

A young boy—the little shepherd—stood beside the seated old man. He was handing the old one a bowl of milk.

While the bishop watched, the old man raised his voice: “Thank you,” he said, “I need nothing more.” And his smile left the sun in order to rest on the child.

The bishop stepped forward. At the sound of his footsteps, the seated old man turned his head, and his face expressed as much surprise as one can have after a long life.

“Ever since I’ve been here,” he said, “this is the first time someone has come to my house. Who are you, monsieur?”

The bishop replied:

“My name is Bienvenu Myriel.”

“Bienvenu Myriel. I’ve heard that name spoken. Are you who the people call Monseigneur Bienvenu?”

“I am.”

The old man continued with a half-smile:

“In that case, you’re my bishop?”

“A bit.”

“Come in, monsieur.”

The conventionalist extended his hand to the bishop, but the bishop didn’t take it. The bishop confined himself to saying:

“I’m happy to see that I was mistaken. You certainly don’t seem ill to me.”

“Monsieur,” replied the old man, “I am about to be cured.”

He paused and said:

“I shall die in three hours.”[143]

Then he continued:

“I’m a bit of a doctor; I know in what fashion the final hour comes. Yesterday only my feet were cold; today the chill reached my knees; now I feel it climbing to my waist; when it reaches the heart, I shall stop. The sun is beautiful, isn’t it? I had myself wheeled out to take a last look at things. You can talk to me; that doesn’t tire me. You do well to come see a man who’s going to die. It’s good that that moment have witnesses. One has one’s fancies; I’d wanted to go just at dawn. But I know that I hardly have three hours left. It will be night. As for that, what does it matter! Dying is a simple matter. One doesn’t need the morning for that. Very well. I’ll die under the stars.”

The old man turned to the shepherd:

“Go to bed. You sat watch last night. You are tired.”

The child went back into the hut.

The old man looked after him and added, as if speaking to himself:

“I shall die while he sleeps. The two slumbers may make good neighbors.”

The bishop wasn’t as touched as it seems that he should’ve been. He didn’t think he felt God in this manner of dying. Let’s say it all, for these small contradictions of great hearts must be shown like all the rest: he who on occasion laughed so readily at “Your Highness,” was rather shocked at not being addressed as Monseigneur, and he was almost tempted to reply “citizen.” An inclination for gruff familiarity came to him, quite common in doctors and in priests, but not customary with him. After all, this man, this conventionalist, this representative of the people, had been a man of worldly power; for the first time in his life, perhaps, the bishop felt himself in a mood to be severe.

The conventionalist, however, gazed at him with a simple warmth, in which one could perhaps make out the humility that is befitting when one is so close to returning to dust.

For his part the bishop, though he was ordinarily wary of inquisitiveness—which in his view bordered on insult—couldn’t refrain from studying the conventionalist with an attentiveness for which his conscience would probably have reproached him in regard to any other man, as its source did not lie in sympathy. To him a conventionalist almost seemed to be beyond the law, even beyond the law of charity.

G., calm, his torso almost upright, his voice vibrant, was one of those grand octogenarians who astonish the physiologist. The Revolution has had a great many of those men, commensurate with the era. One sensed in this old man someone who’d been put to the test. Though so near his death, he’d preserved all the signs of health. There was enough to disconcert death in his clear glance, his firm tone, and the robust movement of his shoulders. Azrael, the Islamic angel of the tomb, would’ve turned back, thinking he’d mistaken the door. G. seemed to be dying because he willed it so. There was liberty in his agony. His legs alone were motionless. The shadows clung to him there. His feet were dead and cold, but his head lived with all the power of life and seemed full of light. G., in that solemn moment, resembled the king in the oriental tale, flesh above and marble below.[144]

A stone was at hand. The bishop sat down on it. He began speaking ex abrupto.[145]

“I congratulate you,” he said in the tone one takes for a reprimand. “You didn’t, in any case, vote for the king’s death.”

The conventionalist didn’t appear to notice the bitter undertone concealed in that phrase “in any case.” He replied. The smile had entirely vanished from his face:

“Don’t congratulate me too much, monsieur; I did vote for the end of the tyrant.”[146]

It was the tone of austerity facing the tone of severity.

“What do you mean?” replied the bishop.

“I mean that man has a tyrant, ignorance. I voted for the end of that tyrant. That tyrant spawned royalty, which is authority rooted in the false, whereas knowledge is authority rooted in the true. Man should only be ruled by knowledge.”

“And conscience,” added the bishop.

“It’s the same thing. Conscience is the amount of innate knowledge that we have within us.”[147]

Monseigneur Bienvenu listened, a bit astonished, to this language, so very new to him.

The conventionalist resumed:

“As for Louis XVI, I said no. I don’t believe I have the right to kill a man; but I feel the duty to exterminate evil. I voted for the end of the tyrant. That is to say, the end of prostitution for woman, the end of slavery for man, the end of darkness for the child.[148] In voting for the Republic, I voted for that. I voted for fraternity, for harmony, for the dawn! I helped bring down prejudices and errors. The collapse of errors and prejudices lets in the light. We’ve made the old world fall, and the old world, that vase of miseries, in being overturned by mankind, has become an urn of joy.”

“Mixed joy,” said the bishop.

“You might say clouded joy, and now, after that fatal return of the past called 1814, vanished joy.[149] Alas, the work had been left incomplete, I agree; we demolished the old regime in practice, we weren’t able to entirely suppress it in ideas. To destroy injustices is not enough; we must change moral principles. The windmill no longer stands, the wind is still there.”

“You demolished. Demolition can be useful, but I distrust a demolition complicated by wrath.”

“The rightful has its wrath, Monsieur Bishop, and the wrath of the rightful is an element of progress. It doesn’t matter; whatever one says about it, the French Revolution is the human race’s most powerful stride since the coming of Christ. Incomplete, so be it; but sublime. It has ‘solved for’ all the social unknowns.[150] It softened the spirits, it calmed, appeased, enlightened; it sent waves of civilization flowing over the earth. It has been good. The French Revolution is the consecration of humanity.”

The bishop couldn’t refrain from murmuring: “Yes? ’93!”[151]

The conventionalist straightened up in his chair with an almost lugubrious solemnity, and, to the extent a dying man can exclaim, he exclaimed:

“Ah! There you are. ’93. I was waiting for that word. A cloud had been gathering for fifteen hundred years. At the end of fifteen centuries, it burst. You arraign the thunderbolt.”

The bishop felt, perhaps without admitting it, that something within him had been hit. Nevertheless, he kept his composure. He replied:

“The judge speaks in the name of justice; the priest speaks in the name of pity, which is nothing but a higher justice. A thunderbolt shouldn’t strike in error.”

And looking steadily at the conventionalist he added:

“Louis XVII?”[152]

The conventionalist reached out his hand and seized the bishop’s arm:

“Louis XVII! Let’s see. For whom do you weep? Is it for the innocent child? So be it then. I weep with you. Is it for the royal child? I ask for reflection. To me Cartouche’s brother—an innocent child, hung by the armpits in the Place de Grève until death ensued, for the sole crime of having been Cartouche’s brother—is no less grievous than Louis XV’s grandson, an innocent child, martyred in the tower of the Temple for the sole crime of having been Louis XV’s grandson.”[153]

“Monsieur,” said the bishop, “I don’t like these comparisons[154] of names.”

“Cartouche? Louis XV? For which of the two do you protest?”

There was a moment of silence. The bishop almost regretted having come, and yet he felt vaguely and strangely shaken.

The conventionalist continued:

“Ah! Monsieur Priest, you don’t love the crudities of truth. Christ, he loved them. He took a rod and swept out the temple. His scourge filled with lightning was a harsh speaker of truths. When he exclaimed ‘Sinite parvulos’ he didn’t discriminate between the little children.[155] It wouldn’t have embarrassed him to bring together the sons of Barabbas and Herod. Monsieur, innocence is its own crown. Innocence has nothing to do with highness. It is as noble in rags as in fleurs-de-lis.”[156]

“That’s true,” said the bishop in a lowered voice.

“I must insist,” continued the conventionalist G. “You’ve named Louis XVII. Let’s understand each other. Shall we weep for all the innocents, for all the martyrs, for all the children, for those down below as for those on high? I’m with you. But then, I’ve told you, we must go back farther than ’93, and it’s earlier than Louis XVII that our tears must begin. I shall weep with you for the children of kings, provided you weep with me for the children of the people.”

“I weep for all,” said the bishop.

“Equally!” exclaimed G., “And if the scales must tilt, let it be in the direction of the people. They’ve suffered the longer.”

There was another silence. It was the conventionalist who broke it. He raised himself on one elbow, pinched a bit of his cheek between his thumb and his bent index finger, like one unthinkingly does when questioning or judging, and challenged the bishop with a look full of the forces of the death agony. It was almost an explosion.

“Yes, monsieur, the people have suffered for a long time. And then, look here, that’s not all: why have you come to question me and talk to me about Louis XVII? I don’t know you. Ever since I’ve been in this region I’ve lived within these fences, alone, never setting foot outside, seeing no one but that child who helps me. It’s true that your name has reached me, indistinctly, and, I must say, not so unfavorably, but that doesn’t mean anything; clever men have so many ways to deceive the honest good men of the people. By the way, I didn’t hear the sound of your carriage, no doubt you’ll have left it behind the bushes out there at the fork in the roads. I don’t know you, I tell you. You’ve told me you’re the bishop, but that doesn’t tell me anything about your moral character. In short, I repeat my question to you. Who are you? You’re a bishop, that is to say: a Prince of the Church, one of those gilt-edged men, titled, owning estates, with large ecclesiastical incomes—the bishopric of Digne, fifteen thousand francs of fixed income, ten thousand francs in incidentals, total, twenty-five thousand francs—who have kitchens, who have liveries, whose table is plentiful, who eat moorhens on Friday, who strut about in ceremonial coaches, lackeys in front and lackeys behind, and who own palaces and who ride in carriages in the name of Jesus Christ who walked in his bare feet! You’re a prelate; revenues, palace, horses, servants, a fine table, all of life’s sensual pleasures, you have this just like the others, and just like the others you enjoy it; that’s good, but it either says too much or not enough; it doesn’t enlighten me with regard to your intrinsic and essential merit when you come with the likely pretension of bringing me wisdom. To whom am I speaking? Who are you?”

The bishop lowered his head and replied: “Vermis sum.”[157]

“A worm of the earth in a carriage!” growled the conventionalist.

It was the conventionalist’s turn to be haughty, and the bishop’s to be humble.

The bishop resumed gently:

“Monsieur, so be it. But explain to me how my carriage—which is over there a few steps behind the trees—how my fine table and the moorhens I eat on Friday, how my twenty-five thousand francs of income, how my palace and my lackeys prove that compassion is not a virtue, that clemency is not a duty, and that ’93 wasn’t inexorable?”[158]

The conventionalist passed his hand across his forehead as if to dispel a cloud.

“Before I respond,” he said, “I beg you to forgive me. I’ve just been in the wrong, monsieur. You are in my house, you’re my guest. I owe you courtesy. You’re discussing my ideas, it’s befitting that I confine myself to disputing your arguments. Your riches and your pleasures are advantages that I hold over you in the debate, but it’s not in good taste to make use of them. I promise you to no longer employ them.”

“I thank you,” said the bishop.[159]

G. resumed:

“Let’s return to the explanation you asked of me. Where were we? What did you say to me? That ’93 was inexorable?”

“Inexorable, yes,” said the bishop. “What do you think of Marat clapping his hands at the guillotine?”

“What do you think of Bossuet chanting the Te Deum over the dragonnades?”[160]

The response was harsh, but went to its mark with the rigidity of a steel tip. The bishop winced; no riposte occurred to him, but he was offended by this manner of alluding to Bossuet. The best minds have their idols, and they sometimes feel vaguely bruised by logic’s lack of respect.

The conventionalist began to gasp; the asthma of the death throes, which is mixed into the final breaths, interrupted his voice; nevertheless, there was still a perfect mental clarity in his eyes. He continued:

“Let’s say a few more words here and there, I’d like that. Beyond the Revolution, which taken as a whole is an immense human affirmation, ’93—alas!—is a retort. You find it inexorable, but what of the entire monarchy, monsieur? Carrier is a bandit; but what name do you give to Montrevel?[161] Fouquier-Tainville is a scoundrel; but what’s your view on Lamoignon-Bâville?[162] Maillard is terrible, but Saulx-Tavannes, if you please?[163] Le père Duchêne is ferocious, but what epithet will you grant me for père Letellier?[164] Jourdan-Coupe-Tête is a monster, but less so than Monsieur the Marquess de Louvois.[165] Monsieur, monsieur, I pity Marie Antoinette, archduchess and queen; but I also pity that poor Huguenot woman, who, in 1685, under Louis the Great, monsieur, nursing her child, was bound to a pole, naked to the waist, the child held at a distance; her breast swelled with milk and her heart with anguish; the baby, hungry and pale, saw that breast, suffered and cried; and the executioner said to the woman, mother and nurse: ‘Recant!’, giving her the choice between the death of her child and the death of her conscience.[166] What do you say to that torture of Tantalus adapted to a mother?[167] Remember this well, monsieur: the French Revolution did have its reasons. Its wrath will be absolved by the future. Its result is a better world. From its most terrible blows there emerges a caress for the human race. I cut myself short. I stop, I have too great a lead on you. Besides, I’m dying.”

And no longer looking at the bishop, the conventionalist concluded his thoughts with these few calm words:

“Yes, the brutalities of progress are called revolutions. When they’re over, one recognizes this: that mankind has been treated harshly, but that it has advanced.”

The conventionalist didn’t suspect that, one by one, he had successively conquered all the bishop’s inner defenses. One still remained, however, and from this entrenchment, the supreme resource of Monseigneur Bienvenu’s resistance, issued these words, in which reappeared nearly all the harshness of his opening:

“Progress should believe in God. The good cannot have an impious servant. One who is an atheist is a poor guide for humanity.”

The old representative of the people didn’t reply. He was trembling. He looked at the sky, and a tear slowly gathered in his eye. When the lid was filled, the tear trickled down his ashen cheek, and he said, nearly stammering, quietly and talking to himself, his eyes lost in the depths:

“Oh, thou! Oh ideal! Thou alone existeth!”[168]

The bishop experienced a kind of indescribable shock.

After a pause, the old man raised a finger toward the heavens, and said:

“The infinite exists. It is there. If the infinite had no self, the self would be its limit; it wouldn’t be infinite; in other words, it wouldn’t exist. But it exists. Therefore it has a self. That self of the infinite, that is God.”[169]

The dying man had uttered these last words in a raised voice and with an ecstatic trembling, as if he beheld someone. After he’d spoken, his eyes closed. The effort had exhausted him. It was obvious that he had just lived in one minute the few hours that had remained to him. What he had just said had brought him close to the one who stands in death. The supreme moment had arrived.

The bishop understood this: time was pressing, it was as priest that he’d come, he’d passed by degrees from extreme coldness to extreme emotion; he looked at those closed eyes, he took that old wrinkled and icy hand, and he leaned toward the dying man:

“This is God’s hour. Don’t you think it would be a pity if we had met one another in vain?”

The conventionalist reopened his eyes. A solemnity overcast with shadow was imprinted upon his face.

“Monsieur Bishop,” he said, with a slow cadence that arose still more, perhaps, from the dignity of his soul than from the ebbing of his strength, “I have passed my life in meditation, study and contemplation. I was sixty years old when my country called on me and ordered me to involve myself in its affairs. I obeyed. There were injustices, I fought them; there were tyrannies, I destroyed them; there were rights and principles, I proclaimed and professed them. Our territory was invaded, I defended it; France was menaced, I offered it my breast. I wasn’t wealthy; I am poor. I was one of the masters of the State, the Treasury cellars were overflowing with coins to the point that we were forced to shore up the walls, on the verge of splitting apart under the weight of the gold and silver; I ate on the Rue de l’Arbre-Sec at twenty-two sous per meal. I succored the oppressed, I comforted the suffering. I tore the cloth from the altar, it’s true, but it was to dress my country’s wounds. I have always supported the human race’s forward march toward the light and I have often resisted progress that lacked pity. I have, on occasion, protected my own adversaries, your fellows. And at Petegem in Flanders, at the very spot where the Merovingian kings had their summer palace,[170] there is a convent of Urbanists, the Beaulieu Abbey of Saint Clare, which I saved in 1793.[171] I’ve done my duty in accordance with my strength, and as best as I could. After which I was chased, hunted down, pursued, persecuted, blackened, jeered at, scorned, cursed, proscribed. For many years now, with my white hair, I have sensed that a good many people think they have the right to despise me; to the poor ignorant masses I wear the face of the damned; and I have accepted, without hating anyone, the isolation of hatred. Now I am eighty-six years old; I am about to die. What is it that you come to ask of me?”

“Your benediction,” said the bishop.

And he knelt down.

When the bishop raised his head, the conventionalists’s face had become august. He had just expired.

The bishop returned home, deeply absorbed in unknowable thoughts. He spent the whole night in prayer. The next day some bold busybodies tried to talk to him about the conventionalist G.; he confined himself to pointing to the sky. From that moment on, he redoubled his tenderness and brotherly love for the children and the suffering.

Any reference to “that old scoundrel G.” made him fall into a singular reverie. No one could’ve said whether the passage of that spirit before his own, and the glow of that grand conscience upon his own, didn’t have something to do with his approach to perfection.[172]

This “pastoral visit” was naturally an opportunity for buzzing for the little local cliques:

“Was that a bishop’s place, the bedside of such a dying man? There was obviously no conversion to expect. All those revolutionaries are relapsed sinners.[173] So why did he go? What was he looking for there? He must have been very avid, then, to experience a soul being carried off by the devil.”

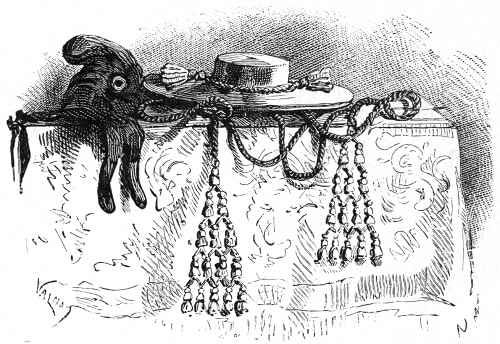

One day a dowager, of the impertinent variety who thinks herself witty, addressed this sally to him: “Monseigneur, people ask when Your Highness will wear the red cap.” “Uh-oh! That’s an intense color,” replied the bishop. “Fortunately, those who despise it in a cap revere it in a hat.”[174]

Footnotes

[136] The French word conventionnel refers to a member of the National Convention, the legislative and executive body that governed France during the first three years of the French Revolution. The word “conventionalist” has the same meaning in English (among other things).

[137] It is unclear why Hugo obfuscates this name. Perhaps G. was based on a historical conventionalist. Or perhaps Hugo simply wanted to suggest that he was based on a historical personage.

[138] Qu’on se tutoyait: when they used the 2nd person familiar pronoun (tu) and verb conjugations in addressing one another. During the period of the Revolution and the Republic, the familiar second person was widely used with the intent of expressing an egalitarian respect. This practice was horrifying to those who used to enjoy class privileges; under the ancient monarchy, tu was a term the aristocracy would use to speak down to the lower classes, while demanding to be addressed themselves with the formal vous.

The linguistic distinction is more complex than a class distinction; in particular, tu was (and is) used to express intimacy between close friends and family. It is so important that French has dedicated verbs, tutoyer and vouvoyer, to refer to the use of tu and vous, respectively.

[139] The use of citoyen (“citizen”) was another hallmark of the revolutionary period, when any person could address any another simply as “citizen” to underline the fact that the former social classes were now irrelevant.

[140] “... but nearly so” (... mais presque) probably refers to fact that there were two successive votes by the Convention, the first on whether the king was guilty, and the second, two days later, on his sentence. To think of these two votes as “nearly” the same (as Hugo says was the case for Digne’s gossips) is to ignore the bitter divisions over the king’s sentence. Although the Convention voted unanimously—693 to 0 with 49 abstentions—for the king’s guilt, they only approved his death sentence by the relatively slim margin of 387 to 334.

[141] When the Bourbons were restored to the throne of France in 1815 (see P1B3Ch1), the members of the Convention who had voted to execute Louis XVI were exiled from France.

[142] “Antipathy”: the word Hugo uses here is éloignement, which in many cases simply means remoteness or distance. The TLFi, however, gives another usage, and cites this very sentence as an example: “Lack of intimacy, familiarity, sympathy for someone.”

[143] The conventionalist has a talent for thought-provoking antitheses. He contradicts the bishop (to be cured is to say one is indeed ill)—and then contradicts himself, leaving us to consider how death might be considered a cure.

[144] In the Arabian Nights, the “Young King of the Black Isles” was afflicted in this fashion by a sorcerer’s curse.

[145] This is a combination of rhetorical terms from both French and Latin that would be obscure for most readers of any language. The French text is: “L’exorde fut ex abrupto,” with the last two words in italics since they are Latin. The sentence is an expression in the vocabulary of formal rhetoric. Exorde (or “exordium” in English) refers to the opening of an oration; ex abrupto is Latin for “without preamble.” The point of these rhetorical terms is, in effect, Hugo’s own exordium, telling us to expect a serious contest of ideas and words.

[146] Another antithetical retort. The exact phrase the conventionalist uses, la fin du tyran, appears to mean the same thing as the bishop’s la mort du roi. But the word fin means “end” as well as “death,” and as he will go on to explain, by tyran (“tyrant”) the conventionalist does not mean the king.

[147] Here there is some untranslatable wordplay in the French: La conscience, c’est la quantité de science innée que nos avons en nous. The concept of “knowledge” would typically be expressed in French by the noun savoir, but the conventionalist uses the somewhat ambiguous word science. In French, this word means both “science” in the usual English sense, as well as the totality of knowledge acquired through experience and study. Hugo seems to have chosen that word in order to be able to antithetically compare and contrast the similar words science and conscience. The effect is lost in English unless science is rendered (imprecisely and therefore confusingly) as “science.”

[148] A formulation that echoes the Preface: “the degradation of man through systematic destitution, the debasement of woman through hunger, and the atrophy of childhood through darkness.”

[149] Recall that after the fall of Napoleon in 1814 the monarchy was restored in France, although in a form somewhat constrained by a constitutional charter. Hugo will have much more to say about this later on.

[150] Hugo uses a metaphor from algebra: dégagé toutes les inconnues sociales. When the verb dégager (“to free, release, extract”) is used with the object inconnu (unknown or stranger), it means to solve for an algebraic unknown by isolating it on one side of an equation.

[151] 1793 was the year when the Reign of Terror began. (Recall the reference to ’93 in I.i.1.) About 40,000 people were executed in less than a year as the courts and the guillotines were used, not just against the French aristocracy, but also by the revolutionary factions against each other.

[152] The son of Louis XVI, who died in prison while only a young child during the French Revolution. Some popular traditions held that he was beaten by his jailer.

[153] Louis Dominique Cartouche was a French robber and murderer who was tried and executed in 1721. His gang was executed over the next several months. His younger brother, although alleged to be a member of the gang, wasn’t condemned to death. He was sentenced only to be hung for two hours in the manner Hugo describes, but he died in the course of that punishment.

[154] “Comparisons”: Hugo uses the word rapprochements, generally meaning the physical bringing together of multiple things. It also means the mental bringing together of things to consider similarities, differences, and logical relationships, one of the hallmarks of Hugo’s thought and writing.

[155] Latin: “Suffer the little children” or “Let the little children” as in Mark 10:14; in the King James Version: “Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God.”

[156] Barabbas is a biblical character, the thief whom Pontius Pilate released when he sentenced Jesus to death, e.g. Mark 15:15 (KJV): “And so Pilate, willing to content the people, released Barabbas unto them, and delivered Jesus, when he had scourged him, to be crucified.”

This is a brilliant integration; the conventionalist takes his previous coupling of Cartouche’s young brother and Louis XVI’s son, and projects it back to Biblical times, where he initially relates it to Christ’s famous injunction, and then the sons of King Herod and the thief Barabbas. He uses the French word dauphin for both of those sons (rather than the more common term fils) to reinforce the comparison; “dauphin” is the generic term for the heir apparent, or oldest son, as well as (when capitalized) the royal title of the French king’s oldest son. Finally, he brings us back to the present day by contrasting the rags of the poor (symbolizing the wretched kin of Cartouche and Barabbas) and the royal emblem of the fleur-de-lis (symbolizing the royal children of Louis XVI and Herod).

Note that as part of this integration, Hugo has the conventionalist use the verb rapprocher for “bring together” (the sons of Barabbas and Herod), rebuking the bishop’s use of the related noun rapprochement.

[157] Latin: “I am a worm”; a quote from Psalms 21:7 (KJV): “But I am a worm, and no man; a reproach of men, and despised of the people.” In Latin: ego autem sum vermis et non homo opprobrium hominum et dispectio pebis.

[158] The word inexorable in French generally means much the same thing as “inexorable” in English: inflexible, pitiless, or relentless; but it also—like many French words—has a pertinent religious connotation: that which cannot be touched or altered by prayer.

[159] There’s a remarkable symmetry and poignancy to this moment. The bishop’s poverty and asceticism—so factually at odds with the conventionalist’s assumptions—are, by the same token, the advantages he would hold in this debate, if he were to openly declare them, but in the same spirit of courtesy (as well as humility) he silently chooses not to do so, and accepts the conventionalist’s reproach along with his apology.

[160] Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627-1704) was a French bishop and orator during the reign of Louis XIV. The “dragonnades” refer to a policy pursued under Louis XIV of housing dragoons in the homes of Huguenots (French Protestants), with the goal of harassing their involuntary hosts into converting to Catholicism.

[161] The old conventionalist begins enumerating a series of revolutionary figures along with their royalist counterparts. Jean-Baptiste Carrier (1756-1794), (the “bandit”) was a revolutionary leader responsible for slaughtering hundreds of Royalists. His Royalist counterpart, Nicolas Auguste de La Baume, Marshal of France and Marquis de Montrevel (1645-1716), had razed hundreds of Huguenot Protestant towns and sent Protestants to the galleys in the late 1600s, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Note that the Edict of Nantes, its revocation, and the massacres of the Huguenots will all come again up in Les misérables. The Edict (1598) protected the rights of the Huguenots for nearly a century; when Louis XIV revoked it in 1685, some 400,000 French Protestants fled the country.

[162] Antoine Quentin Fouquier de Tainville (1746-1795) was the revolutionary prosecutor of Queen Marie Antoinette and many other political figures. Nicolas de Lamoignon de Baville (1648-1724) was an ardent persecutor of Protestants after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

[163] Stanislaw-Marie Maillard (1763-1794), was a revolutionary police administrator and judge. Gaspard de Saulx de Tavannes (1505-1573) played a role in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of French Protestants in 1572, when several thousand Huguenots were killed over a period of a few weeks.

[164] Le père Duchêne was a revolutionary newspaper that published denunciations that frequently led to trials and executions. Its founder and editor, Jacques René Hébert (1757-1794) was also sometimes called père Duchêne. Père Michel Le Tellier (1643-1719) was a powerful Jesuit priest under Louis XIV.

[165] Mathieu Jouve Jourdan (Coupe-Tête) (1746-1794) was a revolutionary military figure behind a massacre in Avignon. François le Tellier, Marquis of Louvois (1641-1691) served as King Louis XIV’s war secretary and architected a “scorched earth” campaign against the Rhineland in early 1689 in which dozens of towns and villages were burnt down.

[166] This incident is recounted by the French historian Jules Michelet (1798-1894) in his book Louis XIV et la Révocation de l’édit de Nantes (1860):

Another ordeal: they tied up a nursing mother and they held her suckling baby who was crying, pining, dying, at a distance. Nothing could be more terrible, all of nature revolted, the pain, the excess of that breast that was burning to nurse, the violent transport of the brain that that produced, it was too much ... She lost her head. She was no longer aware of anything, and said everything they wanted in order to be untied, to go to him and nurse him. But, with that happiness, what regrets! The child, with the milk, received torrents of tears.

[167] Tantalus, in Greek mythology, was condemned in the afterlife to stand in a pond that drew back from him when he stooped to drink, and under a fruit tree whose branches did the same when he reached up to pluck some food.

[168] G. addresses God in the second person familiar in the French. This is usually impossible to translate into English’s second person familiar, as to do so would sound like archaic religious dialog; but in this context that is completely appropriate.

[169] Philosophic argument can be difficult to render precisely in any language. Here is the conventionalist’s argument in French:

L’infini est. Il est là. Si l’infini n’avait pas de moi, le moi serait sa borne; il ne serait pas infini; en d’autres termes, il ne serait pas. Or il est. Donc il a un moi. Ce moi de l’infini, c’est Dieu.

This is a form of metaphysical argument for the existence of God, reminiscent of theology’s “ontological” argument; in effect, it says: the infinite exists (why? behold! it is “there”); and, to be infinite, it can have no limits. If it didn’t possess a self (the pronoun moi used as a noun), that is to say, a mind or consciousness, then it would be limited in that respect. Therefore it must have one, and that mind of the infinite, then, is God.

[170] The Merovingian dynasty ruled part of France from about 450-750.

[171] This is not a historical event. There was such an abbey in Petegem, but it was shut down in 1783 by order of Joseph II (1741-1790), Emperor of the Holy Empire from 1780-1790, as part of his Enlightenment-inspired policy to subordinate the church to the state.

[172] Recall the bishop’s words from his encounter with Napoleon in I.i.1: “Each of us may benefit.” We have already seen other such fateful encounters with unforeseen benefits: between the bishop and the “mountebank,” and between the bishop and Cravatte; this is a recurring motif in Les misérables.

[173] In the French, a relaps; in Catholic doctrine, one who falls back into an acknowledged sin. It’s not clear why this (even if true) would preclude a deathbed confession or conversion, and certainly the bishop did go there with the hope of reconciling the dying man with God.

[174] The “red cap” refers to a soft knit red conical hat worn by the revolutionaries; the “red hat” is the cardinal’s galero. (The illustration at the end of the chapter shows the two side by side on a table.)

© 2023 Steve Wright